In January 1947 a Rylstone mother, Flora Clarke of Mt Brace, received a letter which possibly gave closure for her grief, if anything could. In April 1941 Flora had waved goodbye for the last time to her daughter Mary, who headed overseas to serve in military hospitals. Sister Mary Clarke carried the good wishes and accolades of family and community. The Rylstone Sub-branch had made her guest of honour at the Anzac Day dinner, the Welfare Unit presented her with a leather writing case and the Younger Set had given her a pair of stockings (at a premium in war-time).

Just 12 months later the headline in the Mudgee Guardian announced Mary was a prisoner of war. War is not reliable though, nor are the hopes of a family. By October 1942 the military had posted her ‘Missing’ in the Singapore campaign. Two years later the headline read ‘Brave Nurse Passes On Sister Mary Clarke Drowned’. In January 1945 the family received, from the Minister for the Army, a letter of condolence and explanation – after careful examination of the evidence of a number of missing nurses in Malaya and no communication from them, the army believed they lost their lives after aerial bombing of their transport near Sumatra.

The army stuck with facts, as they should. But that leaves space for imagining. Was her death quick? Did she die alone? Was she blown to pieces? How long did she survive? Was she terrified? Is there any possibility she could still be alive?

One day in late January 1947 Flora opened a typed two-page letter that began, ‘Dear Mrs Clarke…I was a friend of your daughter Mary…was with her when she was last seen.’

In great detail Betty Jeffrey described how on Thursday 12 February 1942 a group of 65 nurses and many civilians left Singapore on the Vyner Brooke ‘a tiny ship not much bigger than a Manly ferry’. Two days later in the middle of the night it was bombed and sunk by Japanese bombers. In the mayhem of survival in rough seas and sinking life boats, Mary and Betty ended up on a raft holding 7 nurses and a number of civilians including 2 slightly wounded children. They took it in turns to paddle with pieces of packing case or swam close to the raft or hung on to rope attached to it. They aimed for the shore but time after time, as they got close, currents carried them back out to sea. Then suddenly the raft and 4 swimmers became separated. ‘The raft was caught in a current that missed us.’ The swimmers with lifebelts were unable to catch the raft. It was carried out to sea again. That was the last time Betty saw Mary and four other sisters. On reaching shore after two more days, Betty was sent to a prisoner of war camp.

‘I felt sure they would turn up,’ she wrote. There it is again, unreliable hope. What she did know though was what a mother would want to know. In the letter Betty wrote about their ‘grand trip’ over to Malaya and off-duty in Malacca. ‘Mary was a sweet girl always so happy and bright and she was still chatting away gaily when I saw her last.’ She explained that she had so often wanted to write to Mary’s mother but only got ‘your address last night’. She wrote, ‘I hope this dreadful story has told you what you must want to know’.

It was a letter full of courage, the courage of nurses lifting spirits, courage when hope faded on the raft close to shore, courage surviving in a POW camp, and courage to write such a letter. Betty concluded, ‘I am terribly sorry we could not bring her home to you.’ As if she could. It is survivor’s guilt, unwarranted, needless. However perhaps it gave Betty the necessary motivation to write her book White Coolies (published in 1954 and reprinted in 1993) ‘for those nurses who did not return’.

I like to think that letter gave Flora the closure needed to order a stained glass window from John Radecki to memorialise her beloved daughter lost at sea. The window was dedicated to St John the Apostle on 8 January 1948, 12 months after Flora received the letter. Though theologians are not in agreement about St John, he is thought by some to be a brother of James, cousin of Jesus and author of the Gospel of John. St John was also called the beloved, and that is surely why Flora chose him to memorialise her daughter.

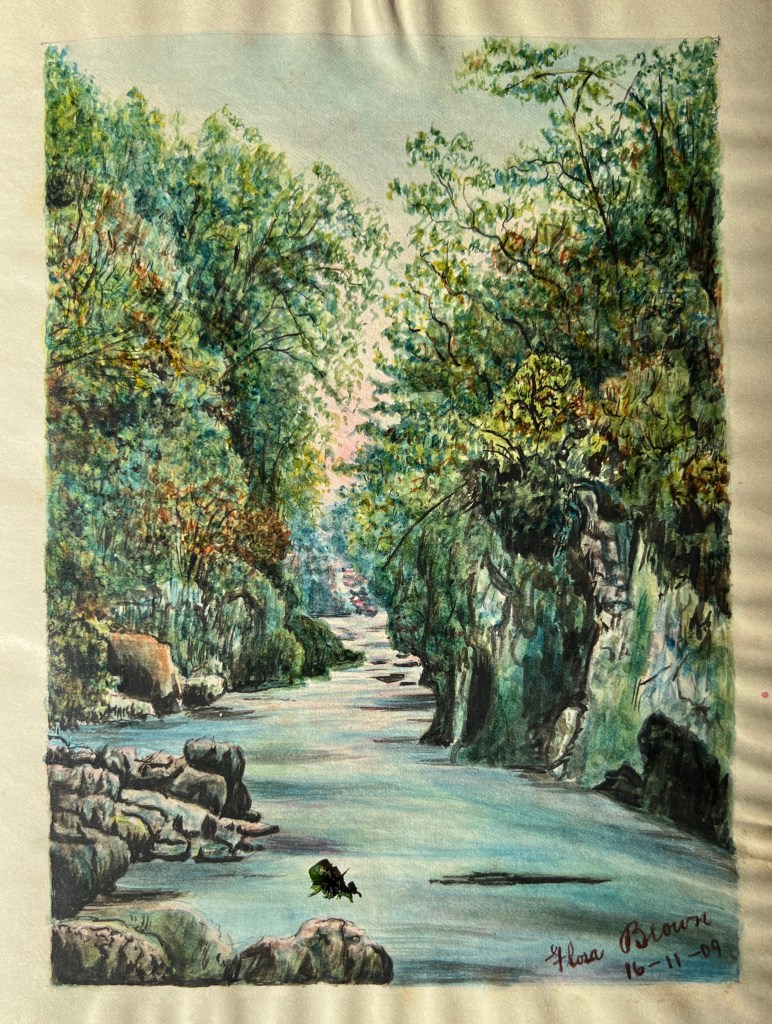

I know little about Flora, except through her entries in her sister Mary’s Album. There, at the age of 27, she demonstrated a talent in art, found comfort in prayer and was open-minded in outlook. The prayer she chose was from the Carmelite nun St Teresa of Avila.

Let nothing disturb thee,

Nothing affright thee,

All things are passing;

God never changeth;

Patient endurance

Attaineth to all things;

Who God possessth

In nothing is wanting;

Alone God sufficeth.

Official military photo of

Sister Mary Clarke

Flora’s painting of wrens in her sister’s album

<

div dir=”ltr”>A wonderful story of sacrifice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Michael

LikeLike

More on those who survived (at least) the sinking of the Vyner Brooke – and Betty Jeffreys – whose radio serialisation of White Coolies I recall listening to as a boy. And the other nurses who ended up on Radji Beach on the island of Bangka further down the coast and who were massacred there – all dying except for Vivian Bullwinkel – who therefore lived to tell that tale – and among those dying there an aunt of film director Philip Noyce – Katharine NEUSS (the original German spelling – Philip’s father having changed the spelling to fit the pronunciation) and of a friend now in her retirement in Yamba – who last year joined a family group and went to Bangka and to a family ceremony in memory of Kate Neuss on Radji Beach.

I note again that Jan (or John) Radecki get’s a further mention. I will forward this to his great grand-daughter in Sydney as well as to Kate Neuss’ niece in Yamba.

Thank-you for another beautiful essay on Kandos and district history connections.

Jim

LikeLike

Jim you have an encyclopaedic knowledge and memory to go with it. I am in awe. Thank you for sending on my blogs.

LikeLike

Thank you for a very moving story Colleen. I did not know there was a ‘local’ nurse on the Vyner Brooke. Such a huge tragedy. Thank you too for the well researched article on the stained glass windows at St James.

Karlyn R

LikeLike