This is the story of three New Zealanders: a chairman, a general manager (who was also chief engineer) and an architect.

I will start with the engineer who became General Manager, Frank Oakden, born in the industrial town of Warrington England in about 1857, who migrated to New Zealand as a young man, and married his shipboard romance, Kate Blundell in 1883. While still in his twenties he got himself noticed in the Dunedin press as an inventor, taking out patents for such things as a tram-rail cleaner, a safety catch for lifts, reversible chain belting, a rabbit tilt-trap, an automatic revolving nozzle for dredging, a wire strainer (for straining wire fences) and improvements in car-fenders (the T-Model Ford was still five years away!).

At the age of 31 Oakden became General Manager of Milburn Cement and Lime Company and its three company worksites at Dunedin, Otago Peninsula and Canterbury. His career spiralled up from then on. As GM he travelled not just around New Zealand but took at least three overseas trips that included France, Denmark, England, Japan, China, Russia, Germany, England and America, where he learnt about the latest cement-making processes and purchased the latest machinery for the Milburn factory.

It’s not surprising that his reputation in cement making led to him being headhunted in 1911 by the NSW government, to report on the best site for the government’s proposed state cement works. That task took him to many areas in NSW including the Rylstone area but he eventually selected Homebush Bay as the most suitable location. Those cement works didn’t eventuate but there were entrepreneurs in the state who wanted to get in on the action. A little more than a year later the NSW Cement Lime and Coal Company was formed to establish cement works near Rylstone. Frank Oakden was appointed General Manager.

He was involved in the company for eleven years and in 1924 took on the role of consulting engineer for the rival cement works at nearby Charbon, returning to New Zealand in 1929.

I’ll come back to him in a while.

The next Kiwi in this trio was James Angus. He too was a migrant from Britain, but he was a Scotsman, born in 1836, raised on a farm near the small town of Auchterarder in Perthshire, where he became a sawyer and turner. Soon after marrying Charlotte de Vernet Moodie at the age of 27, they migrated to the cold Southland region and settled at Invercargill, where Angus started a sawmill business.

Railways were becoming a big thing in the colonies around this time and James Angus could see that two resources were essential: timber for sleepers and coal to drive the steam trains. He formed Angus and Company to supply both. He made a success of this business and in the process learnt a lot about railway construction. Better opportunities in Australia drew him there with his family to establish a career in tram and railway construction. It included his part in building the rail between Wallerawang and Mudgee in 1884, right past where he would, in three decades, build a cement industry. His rail career done, he moved into wine making, purchasing the Minchinbury estate at Rooty Hill and employing Leo Buring to produce the famous Minchinbury champagne. Selling it in 1913 he helped form the company, NSW Lime, Cement and Coal, with himself as Chairman. And so Kandos was born.

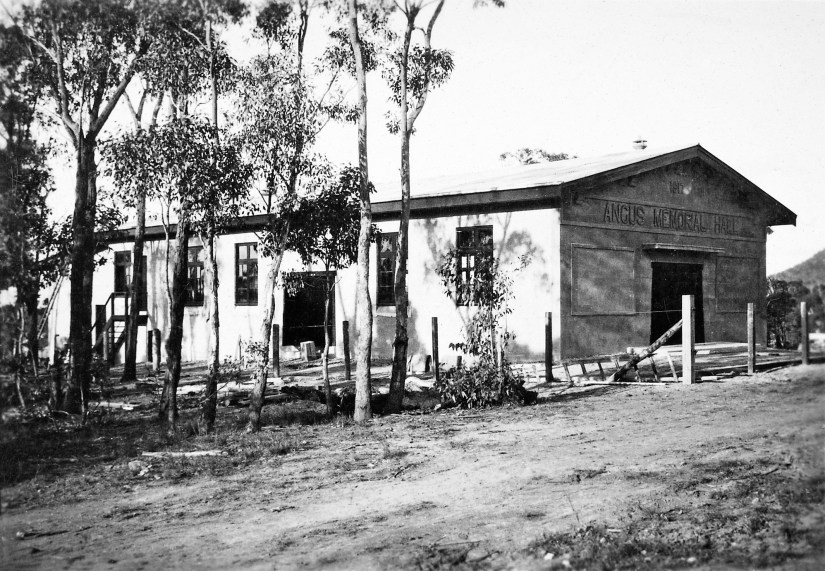

Angus’s connection with Kandos ended abruptly on 12 April 1916 when he was accidently killed by an express train at Rooty Hill station. His son had the Angus Memorial Hall built at Kandos in his honour.

So, we come to the third New Zealander, Stanley Jeffreys, another Briton, born in Farnworth England, who migrated with his parents Julius and Emily to Dunedin, where his five siblings were born. Jeffreys started as a draftsman, got his architectural training through the International Correspondence Schools of Scranton Pennsylvania USA and set himself up as an architect, designing houses, office buildings, hotels and workers’ dwellings throughout New Zealand. Perhaps he was head-hunted by Angus or Oakden but in any case he was employed as architect/draftsman in 1915 to provide plans for buildings at the cement works, and in Kandos. He left Kandos and retired to Collaroy in 1926.

These three men established themselves during La Belle Epoque era, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – up to World War 1. It was an age of optimism, innovation, peace, travel and industrial expansion, an age of perfect confidence in human progress. It was also an age when workers (and women) were beginning to flex their muscles, and employers were showing greater responsibility towards the workforce.

As you can see all three men were highly skilled and motivated. So let’s assess what they contributed to Kandos. The man who had the most influence initially, and probably contributed the majority of £200,000 pounds to establish the company, was Chairman, James Angus. It was he who steered the vision, values and principles of the company and imparted the company culture. Here are some of the things said about him – “true worth and nobility of character…[who] by his industry, tact, perseverance and good common sense rose to the position of honor in the commercial world…as an employer of labor he was good to his men. He treated them as they ought to be treated and they respected him for it.” It is surely his influence that led to relatively peaceful relations between workers and company for nearly a century.

The company under Angus decided that though Kandos would begin as a company town, it would not be the company’s town. The company bought the land and had it surveyed and laid out, with wide, named streets, and quarter acre blocks. Then they held the first auction. The lots were freehold, so that workers could establish their homes and families in a pleasing environment, expecting long-term employment. There would be parks and the company would help establish infrastructure. For example, James Angus ensured there was a railway station close to the town, away from the works’ siding; and he organised for the platform to be built with a small building attached even before town lots went to auction. Early on, electricity was provided to the station and main street.

The town was named Candos, it is said, by Angus’s daughter using the initials of company officials (A for Angus, O for Oakden); and renamed Kandos (after an objection by the Post Master General). The first streets were also named after company officials, Angus for the main street (though there is no Oakden Street).

In the three years that Angus was chairman, 150 men were employed; 3 dams were built; the aerial ropeway and double tramway from coalmine to railway and tramway to shale mine were in operation; the stone crusher was erected and operating; offices and temporary accommodation were completed; the power house was built and steel kilns and gas plant (for lighting) installed; machinery costing £27,500 was contracted.

While Angus and his board directed the company, it was Frank Oakden who as General Manager oversaw the works at Kandos (until a works manager was appointed). It was Oakden as engineer, with his innovative mind and risk-taking attitude, who got the infrastructure in place. And when the machinery was held up in Africa due to the war, it was Oakden who sailed off to America and Europe to order more.

Stanley Jeffreys’ stamp on Kandos is less obvious and less well known, but significant nevertheless. We can suppose that, as company architect, all works’ premises and company houses were designed by Jeffreys. The Mudgee Guardian also makes reference to a number of private buildings (though doesn’t identify them). At least two important town buildings were designed by him: St Lawrence’s Church (1919) and St Dominic’s Church (1921). He also acquired land from John Donoghue, had it subdivided (the Jeffreys subdivision), and named its only street, Stanley. Both Jeffreys and his wife involved themselves in the Kandos community with generous donations and membership of various associations.

Australia and New Zealand have had what could be described as a sibling relationship: usually comfortable and co-operative, occasionally antagonistic, with the older sibling sometimes adopting a superior posture and the younger one, asserting independence. Thus Australians have never believed that New Zealanders could better them (except at football). And in 1901 New Zealanders rejected federation with Australia.

Kandosians might therefore find it hard to accept that three New Zealanders contributed more to the foundation of Kandos than any three Australians. Is this up for discussion?

Thank you to Lynne Kelsall, a Kiwi import, who suggested the topic “A Kiwi Perspective” (tongue-in-cheek perhaps).

James Angus at about 65 circa 1901.

Courtesy of Lorance Angus.

Taken from Daily Telegraph 27/10/2014

Very interesting Col – we are amazed that you can find the time to do all this. Your talents are endless! Love Chris and Kathy XO

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

Many thanks Kath. Sometimes I wonder how long I can keep it up!

LikeLike

Wonderful research again Colleen. I wonder if these three men have descendants that call themselves Australian but could very well be New Zealanders!!

LikeLike

Thank you Carol. Yes dual citizenship does restrict our pool of potential politicians. It needs to change.

LikeLike

My grandfather Walter Murphy built both St Dominic’s and St Laurence’s.

LikeLike

Yes I was reminded of him building St Dominic’s the other day. Don’t think I knew he built St Lawrence’s. Thank you.

LikeLike

It’s hard to seek out knowledgeable people on this subject, but you sound like you realize what you’re talking about! Thanks

LikeLike